The Dynasty You’ve Never Heard Of

One Italian dynasty owns Ferrari, Jeep, Chrysler, Maserati, and The Economist. Their soccer team is valued at over $2 billion. They hold the reins to Italy’s biggest bank. With command over 30% of Italy’s stock market and a workforce of 360,000 people worldwide, the Agnellis wield influence that rivals sovereign nations.

Yet their name remains largely unknown outside Italy.

Calling them Italy’s answer to the Rockefellers does not capture the full picture. This family holds the keys to Italy’s economic engine. Whether the nation prospers or struggles often hinges on decisions made in Agnelli boardrooms. The truly astonishing part? They built this empire through strategic flexibility, aligning with whoever held power at any given moment. Fascists, Allies, Communists—ideology mattered less than survival and growth.

Where Power Never Changes Hands

Power in Italy doesn’t transfer through ballot boxes. It flows through family trees, cascading from Renaissance-era palaces into modern corporate towers. The Benettons built infrastructure empires. The Pirellis dominated manufacturing. The Berlusconis conquered media and politics. Yet none achieved what the Agnellis accomplished.

For over a century, they have been Italy’s industrial aristocracy. Their strategy was simple but devastating: acquire the country’s most iconic brands, embed themselves into national identity, and transform commercial success into political leverage. When Gianni Agnelli’s enterprises accounted for nearly 8% of Italy’s GDP, government ministers didn’t just consult with him. They waited for his approval. Policy proposals lived or died based on whether they served Fiat’s interests.

But every empire has humble origins. Before becoming synonymous with Italian capitalism, the Agnellis were simply another wealthy Turin family with an audacious plan: manufacture automobiles in a nation without proper roads.

A Visionary Gambles on the Future

Italy in 1899 was a study in contrasts. The industrializing north clashed with the impoverished, agricultural south. The nation, unified mere decades earlier, still struggled to forge a coherent identity. Into this turbulent landscape emerged Giovanni Agnelli, a former cavalry officer with an extraordinary gift for recognizing potential in chaos.

While his countrymen clung to traditional ways, Giovanni fixated on combustion engines, velocity, and industrial transformation. On July 11, 1899, he joined a small investor group to establish Fabbrica Italiana Automobili Torino. Fiat.

The first factory launched in 1900 with Giovanni as managing director commanding 35 workers. Their output that inaugural year? Precisely 24 automobiles. This might seem insignificant today, but in 1900 Italy, it was revolutionary. Automobiles remained exotic curiosities. Infrastructure didn’t exist. Consumer demand was nonexistent. Giovanni wasn’t entering an industry. He was inventing one.

Growth came rapidly. Production quintupled by 1904. By 1906, Fiat manufactured over 1,000 vehicles annually and had established a New York dealership before automobile ownership became common in Italy itself. That year, Fiat incorporated publicly. Giovanni’s achievement was remarkable: beginning as the most junior founding partner, he systematically acquired controlling interest by purchasing crucial patents and implementing cutting-edge production techniques that positioned Fiat decades ahead of competitors.

War as Business Strategy

When World War I erupted, Agnelli seized the moment. Fiat’s factories pivoted overnight to wartime production. Turin plants operated around the clock, supplying Italy’s military with trucks, tanks, airplanes, tractors, and diesel engines. By war’s end, over 30,000 workers fueled the effort, catapulting Fiat from 30th to third among Italian industrial giants.

The profits were extraordinary. So were the accusations. Critics blasted Fiat for war profiteering. Giovanni needed political protection and found it in Benito Mussolini, a rising nationalist firebrand. Beginning in 1914, Agnelli funded Mussolini’s movement. When controversy erupted over Fiat’s wartime windfall, Mussolini repaid the favor by clearing the company’s record.

The alliance delivered beyond expectations. By the late 1930s, Fiat employed 50,000 workers and dominated Italian industry. When World War II began, assembly lines again shifted to military production for Mussolini’s forces and, after Italy joined Nazi Germany, for the German war machine.

But as defeat loomed, Giovanni swiftly changed course. He voiced sympathy for the Allies, reading history’s direction. Pure survival instinct. Italian authorities temporarily seized his assets for fascist collaboration in 1945, yet punishment proved brief. Fiat was too crucial to Italy’s economy to undermine, and familial ties ensured his survival, paving the way for the dynasty’s subsequent generation.

The Next Generation: Gianni Agnelli Takes Command

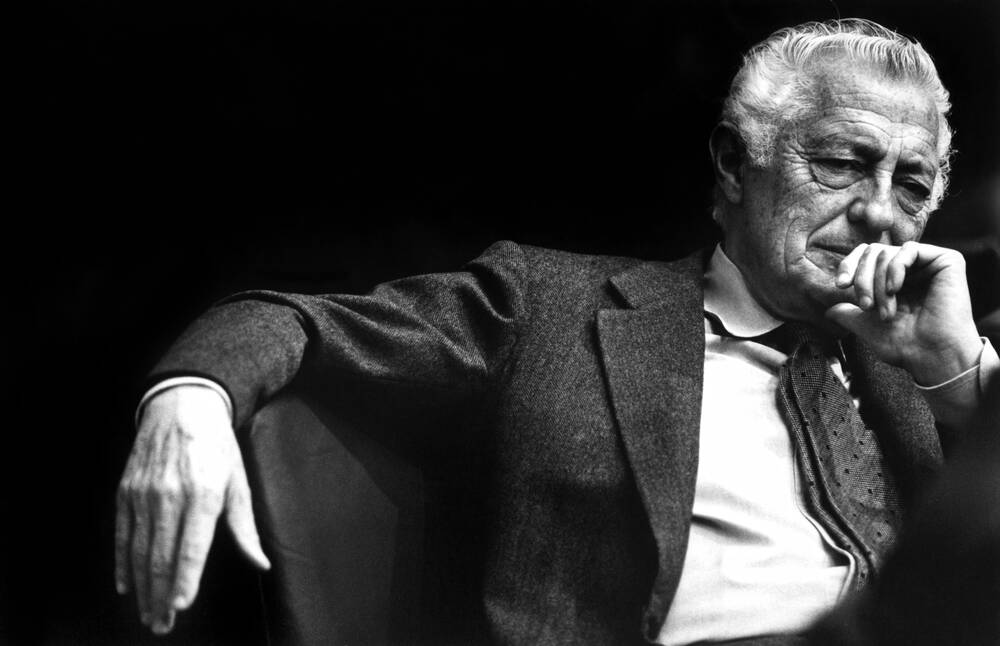

After the war, the empire passed to a new generation. Giovanni’s grandson, Gianni Agnelli, took charge in 1945. Gianni was sharp and ambitious. He knew power had to be earned and then controlled. By 1963, he became managing director, and just three years later, he was chairman and CEO, basically the most powerful industrialist in Western Europe.

Gianni helped drag Italy out of the ruins of war and into the modern age. He was not afraid to cross boundaries. In the middle of the Cold War, he partnered with the Soviet Union in a deal that rewarded his company handsomely. Together, they built a factory capable of producing more than half a million cars a year. This way, he proved that profit could outpace ideology.

That mindset took Fiat global. Under Agnelli, Fiat absorbed Italy’s greatest car names: Ferrari, Alfa Romeo, Lancia, and Maserati. By his final years, Fiat had won seven European Cars of the Year awards and had over 200,000 people working under him.

One in every five Italians working in manufacturing had some link to Fiat or its suppliers. Entire towns revolved around its production lines. A job at Fiat meant stability, status, and belonging to Italy’s post war recovery.

Controlling the Narrative: Media, Data, and Culture

The Agnellis understood that true power extends beyond factories and balance sheets. It lives in what people read, believe, and love.

When Exor paid €102 million for a 43.7% stake in GEDI, Italy’s largest media group, they gained control of La Repubblica, La Stampa, 13 regional newspapers, and multiple radio stations. But John Elkann’s ambitions reached further than his grandfather Gianni’s ownership of La Stampa. In 2015, Exor acquired 43.4% of The Economist Group, securing influence over a publication that shapes how global investors, policymakers, and corporate leaders think about markets and geopolitics.

By 2024, Exor held 10.1% of Clarivate, potentially rising to 17%. This data analytics giant serves universities, corporations, and governments worldwide. In an era where information is currency, the Agnellis positioned themselves at the source, gaining early insight into trends in pharmaceuticals, AI, and patent markets before competitors.

But their most strategic conquest wasn’t intellectual. It was emotional. Since 1923, when Edoardo Agnelli became president of Juventus, the family turned football into a tool for mass loyalty. Victories became symbols of Agnelli dominance, uniting factory workers and executives under one banner.

Fiat’s acquisition of Ferrari began with 50% in 1969 and eventually reached 90% by 1988. This added elite aspiration to working-class mobility. After Ferrari’s IPO, Exor’s deal with Piero Ferrari secured 48.1% of voting rights. Full ownership became unnecessary.

Dynasty or Democracy?

From Turin to Brussels, the Agnellis’ moves extend well beyond cars and sports. They define narratives, industries, and influence. They’ve outlasted monarchies, dictators, and political shifts without ever needing public office.

So that begs the question: Is Europe really built on democracy, or dynasties that just never left?

The Agnellis show how far vision and patience can reach. In a continent still ruled by old money and quiet alliances, they remain one of the few families that turned a national legacy into continental power. And they are not done yet.