The Capitalyst: Can you tell us about your early life and the first moment you realised that photography could be a way for you to document, question, and make sense of the world around you?

Taha: I grew up in Lucknow, surrounded by art, poetry, heritage, and Lakhnavi tehzeeb. My great-grandfather Dr. Wasi Ahmad and my grandfather Dr. Afzal Ahmad were poets and barristers, both protégés of the legendary Arzoo Lakhnavi. My grandfather later founded Anjuman-e-Arzoo, a literary organisation for progressives, artists, and poets, under which my family hosted baithaks, mushaiyaras, and cultural evenings in our century-old home in Lucknow. Poets like Ahmad Faraz, Iftikhar Arif, Bashir Badr, Kaifi Azmi, performers like Begum Akhtar, progressives like Shahnaz Husain and even actors like Prithviraj Kapoor would come stay with us and become part of those unforgettable mushaiyaras and evenings. Unfortunately, I was only able to witness a few of those gatherings before my grandfather passed away. I was in class 7 then. Yet those moments, along with the archives of photographs, letters, and stories from those times I inherited, deeply shaped my earliest understanding of art and culture.

Photography came to me as a way to hold on to these worlds. The first time I used a camera, I realised it could preserve what might otherwise disappear; people, spaces, and histories. Over time, it became my way of questioning, protesting and remembering, continuing the legacy of storytelling I inherited through interdisciplinary methods. For me, my art is both a witness and my voice.

The Capitalyst: What did your introduction to the camera look like? Were there certain people, memories, or images that shaped the visual style you’re now recognised for?

Taha: My introduction to the camera was instinctive more than academic. I first picked up a camera because I liked a girl in my class when I was in art school and wanted to spend time with her, while she photographed in the wild. It was amazing to begin my journey as a wildlife photographer amongst mother nature and human love. What started as a gesture of affection soon became a quiet obsession.

But everything changed when I met my first mentor, Mr. Sandeep Biswas through my professor Mr. Hafeez Ahmed, who too had played an important role in my life. Sandeep Biswas introduced me to documentary photography, and showed me that a camera could be more than a tool. It could be a witness, a voice, a protest and a mirror to society. Under his guidance, I began working with communities, listening to people’s stories, and understanding the ethics of remembrance and representation. It was during this period that I received my first major recognition, The Neel Dongre Grant for Excellence in Photography, which was a turning point in my journey.

Like most artists, I evolved in phases. An artist’s practice transforms with time, experience, and experimentation. After several years of documentary work, I met veteran French journalist Vanessa Dougnac, who introduced me to photojournalism and conflict photography. That path unfolded into another. Soon after, I was discovered by Aradhana Seth, Mira Nair, and Lydia Pilcher, which led me to the sets of A Suitable Boy and eventually into the film industry. One project led to another, Netflix happened, and today I have worked on nearly 15 films and series (national and international) as a film still photographer.

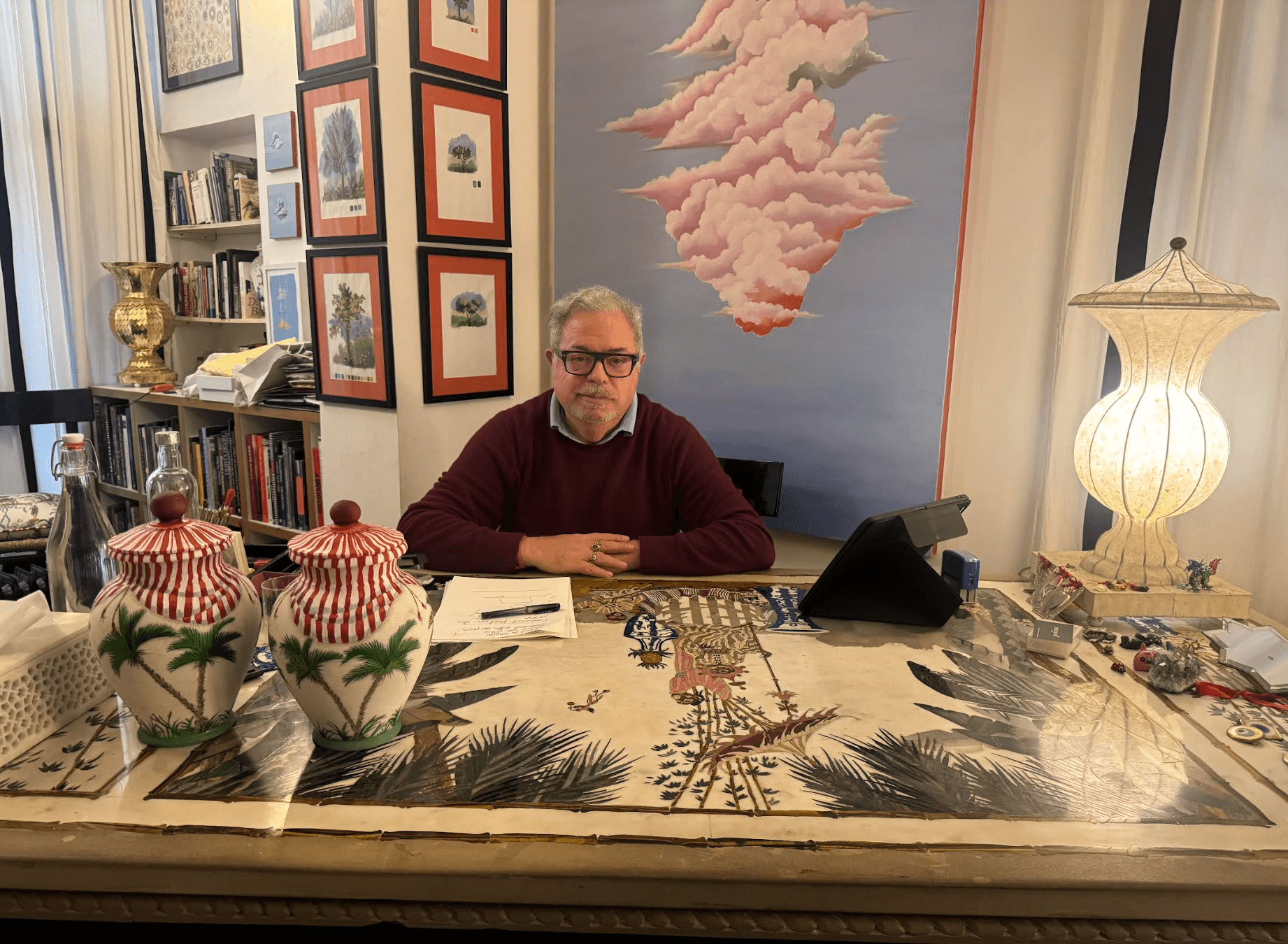

I still remember while working on Kota Factory Season 2, I somehow met Rahul Mishra not as a part of the series though, who encouraged me to approach fashion through my own lens. I later shot his campaign that opened at Paris Fashion Week.

Today, I work across disciplines merging photography with materials like gold, miniature painting, calligraphy, and creating art installations, and immersive experiences rooted in memory, language, identity and heritage. Over the years, I’ve met some incredible people in my life who have shaped my practice, each contributing to my journey in their own way. Shamsi Abbas, Vishal Bhardwaj, Dr. Ali Khan Mahmudabad, Sabika Abbas, Shan and Devyani Bhatnagar, Owais Sultan Khan, Laetitia Colombani, Suvir Saran, Anita Lal, N.K Sharma, Urvashi Kaur and many more. Unfortunately, I can’t name everyone here, but it is only because of them that I have reached a certain position in life. I don’t know where this journey will lead and perhaps that mystery is the most exciting part. What I do know is that I want to push my practice further into cinema. I’ve been developing a film script, and I hope to direct a film in the near future, another chapter, another medium, another way to tell a story.

The Capitalyst: Growing up in Lucknow – a city layered with culture, history, and everyday theatre – how has that environment shaped your sensibilities as a storyteller and image-maker?

Taha: Growing up in Lucknow meant growing up with art, culture, history and poetry. The city is a living archive. It is a place where beauty and decay coexist, where memory is not just remembered but performed. I grew up in a Muslim neighbourhood, and coming from a secular family I was surrounded by Urdu literature, Hindu and Islamic art and old stories. But as I grew up I also witnessed the city changing, becoming increasingly unsecular, where the narratives of my community, our heritage and language were gradually pushed to the margins, often both victimised and villainised.

These experiences shaped my sensibilities deeply and my art practice. They made me aware of silence, memory, and the emotional texture of history. Through my work and artistic approach, I strive to tell these stories of resilience, loss, grandeur, and the quiet strength that endures despite erasure and neglect.

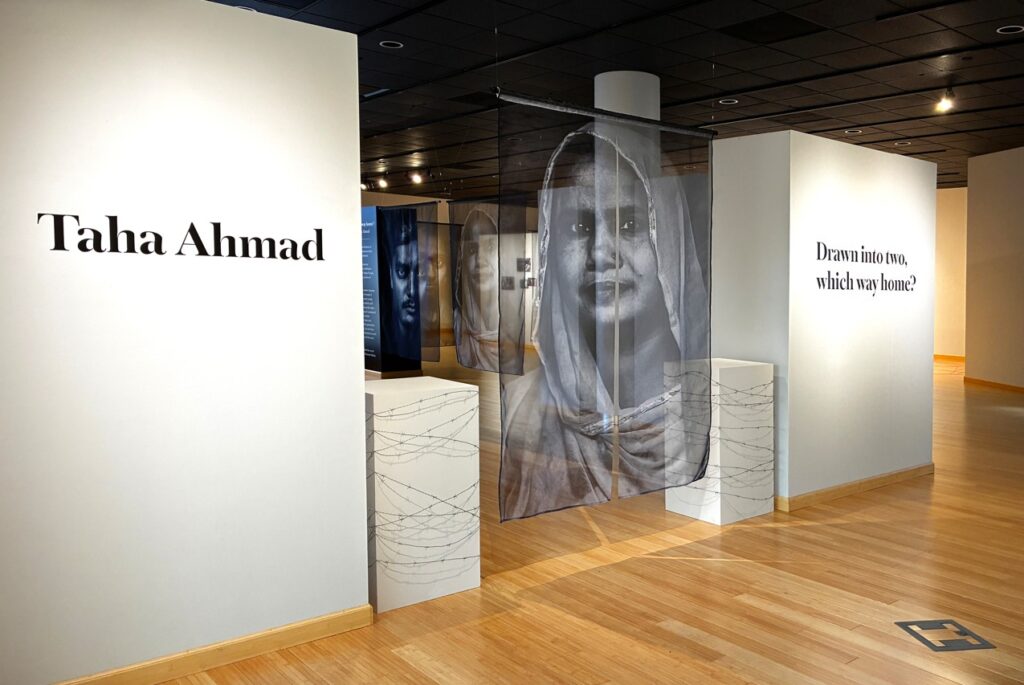

The Capitalyst: Your landmark project Drawn into Two, Which Way Home? takes on the emotional aftershocks of Partition. What compelled you to explore this chapter of history so directly and so personally?

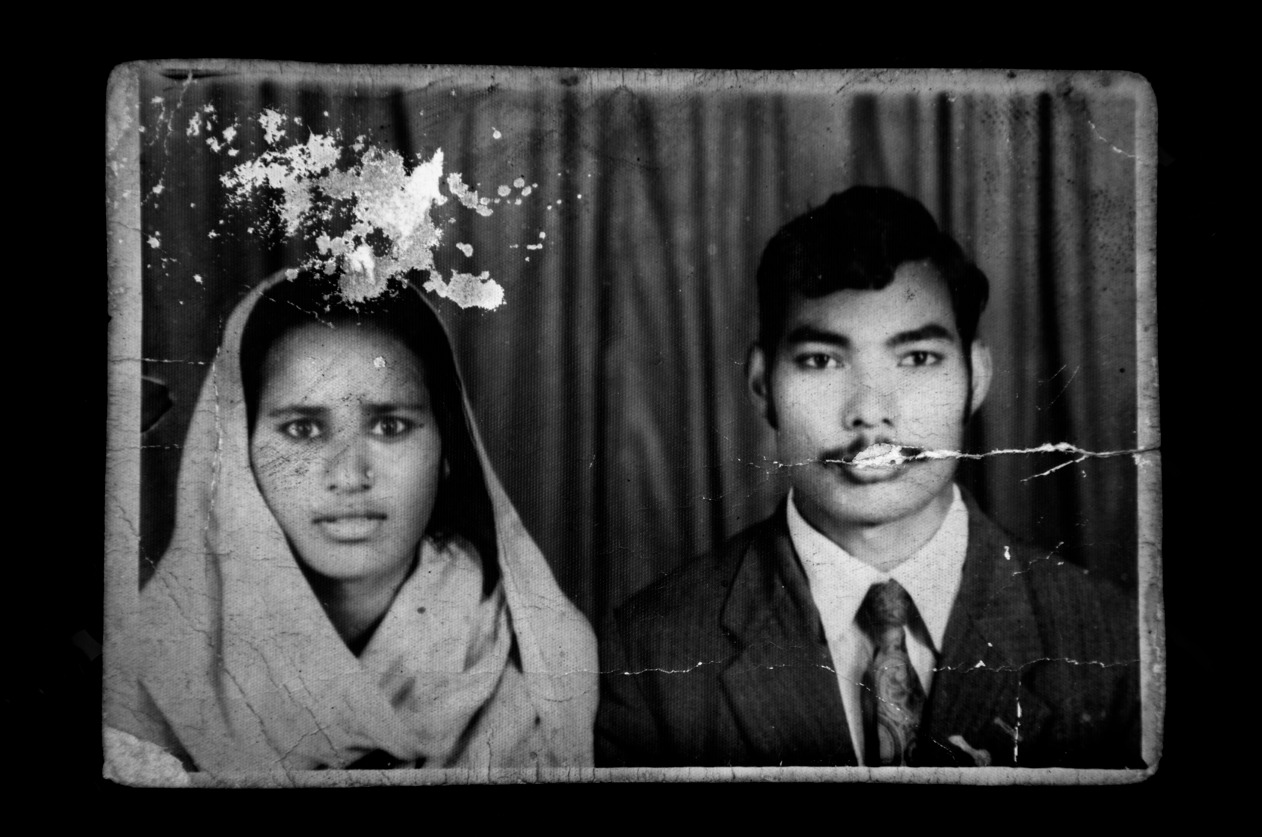

Taha: Partition is not a distant chapter for me, it lives inside my family. On my grandmother’s side, the fracture was literal. Her extended family migrated to Pakistan while her immediate family remained in India. With shifting politics and rising tensions over decades, communication slowly faded, and eventually disappeared. Today, generations later, we no longer know the family that crossed over and they don’t know us. Partition didn’t just displace people, it severed bloodlines, leaving gaps that memory alone cannot fill. From my grandfather Dr. Afzal Ahmad’s side, the rupture was deeply felt. Many of his friends, poets and writers who were a part of Anjuman-e-Arzoo, the literary organisation he founded, either migrated to Pakistan or chose to stay behind. Some never returned, and the circle of voices that once shared poetry under the same roof was divided forever. Partition has always been personal to me, not just as a brutal history, but as inheritance.

Drawn into Two, Which Way Home? came from this intimate place. I started developing the work back in 2018 when I was selected for an Artist-in-Residence programme funded by Arts and Humanities Research Council grant (UK) called Creative Interruptions, Preet Nagar Trust, The University of British Columbia (Canada), The University of Strathclyde (UK) and CRCI (Delhi). But the installation itself took shape later, I would say last year during my conversations with film producer Shamsi Abbas when I received an award from University of Pennsylvania to exhibit my work there in the States. That moment became crucial as I knew I wanted to create something immersive, something that allows viewers to experience, feel the uncertainty, longing, and intergenerational trauma of Partition rather than just observing it. That’s how the latest show in the States came up in collaboration with Shamsi Abbas.

The Capitalyst: In this series, you combine photography, textile, installations, family archives, and oral testimonies. How did you approach weaving all these elements together to reveal Punjab’s lesser-seen realities of identity, memory, and displacement?

Taha: The approach was rooted in both research, my experiences in Punjab and the numerous stories I collected while living at the border area. I wanted to create a layered experience that could capture the complexities of Partition, not just as a historical event, but as a lived memory. I wanted my work to be grounded in contemporary times, addressing the Indian state of Punjab, a region still grappling with complex social, political, and geopolitical challenges, the seeds of which were sown during Partition.

I approached each element of my installation as a thread in a larger tapestry. The photographs became anchors for memory and visual documentation, the textiles a metaphor for displacement and rupture, and the audio piece gave voice to intergenerational trauma. The mirrors and threads were meant for self-reflection, to confront how we, as societies, have often failed to learn from history and how we risk repeating the same fractures across borders with the growing polarisation, religious hatred and social divides in our country.

The Capitalyst: Were there any particular encounters with survivors or families during the Partition project that fundamentally changed your understanding of the event — or your role as a photographer?

Taha: The entire Partition project was built around stories that had largely remained unheard, narratives that never saw the light of day. My role as a visual artist and a photographer went beyond documenting oral testimonies of families displaced or torn apart in 1947. I also wanted to capture how the intergenerational trauma and aftermath of Partition continues to affect contemporary Punjab.

One story that profoundly shaped my understanding and made me unlearn the history I was taught in school was with a family in Preet Nagar. I saw a photograph of two women holding guns, and when out of curiosity I asked about the story behind the photograph, I learned about Nazeera and Aarfa. They were two sisters from a Muslim family in Pul Kanjari village. During the violence of 1947, they lost their brother Arif and father Naseer while defending their family from a mob. To protect their loved ones and the elderly they took up arms and became ‘resisting women, rescuing their family members by confronting and scaring them away. Later that same year, they migrated to Pakistan to escape persecution and discrimination, leaving behind their ancestral home and land. During the migration, Nazeera was abducted by men from the opposite faith but was reunited with her family two years later through the Abducted Persons Recovery and Restoration Ordinance of 1949.

Today, both sisters have passed away, but their story survives within their family in Lahore as a tale of bravery and sacrifice. I created a double-exposure photograph combining their last photo together, shot in 1995, with a portrait of their brother, who died in 1947.

Encountering stories like theirs during my residency changed the way I approached my project. It made me understand and realise how profoundly women contributed and sacrificed at the same time, during Partition, both in acts of resistance and survival, and how their histories have largely been erased in the narratives of both India and Pakistan.

The Capitalyst: Your boxer series has a very different visual language yet still speaks to struggle, identity, and resilience. What pulled you toward the world of young boxers, and how does this series connect to the themes you keep returning to?

Taha: Actually, I haven’t worked on a series about boxers. My recent project, which I have been creating since the last three and a half years, is scheduled to be released next year. It is a collection of 25 artworks that takes on a different yet deeply resonant theme, the disappearance, villianisation and erasure of the Urdu language in India.

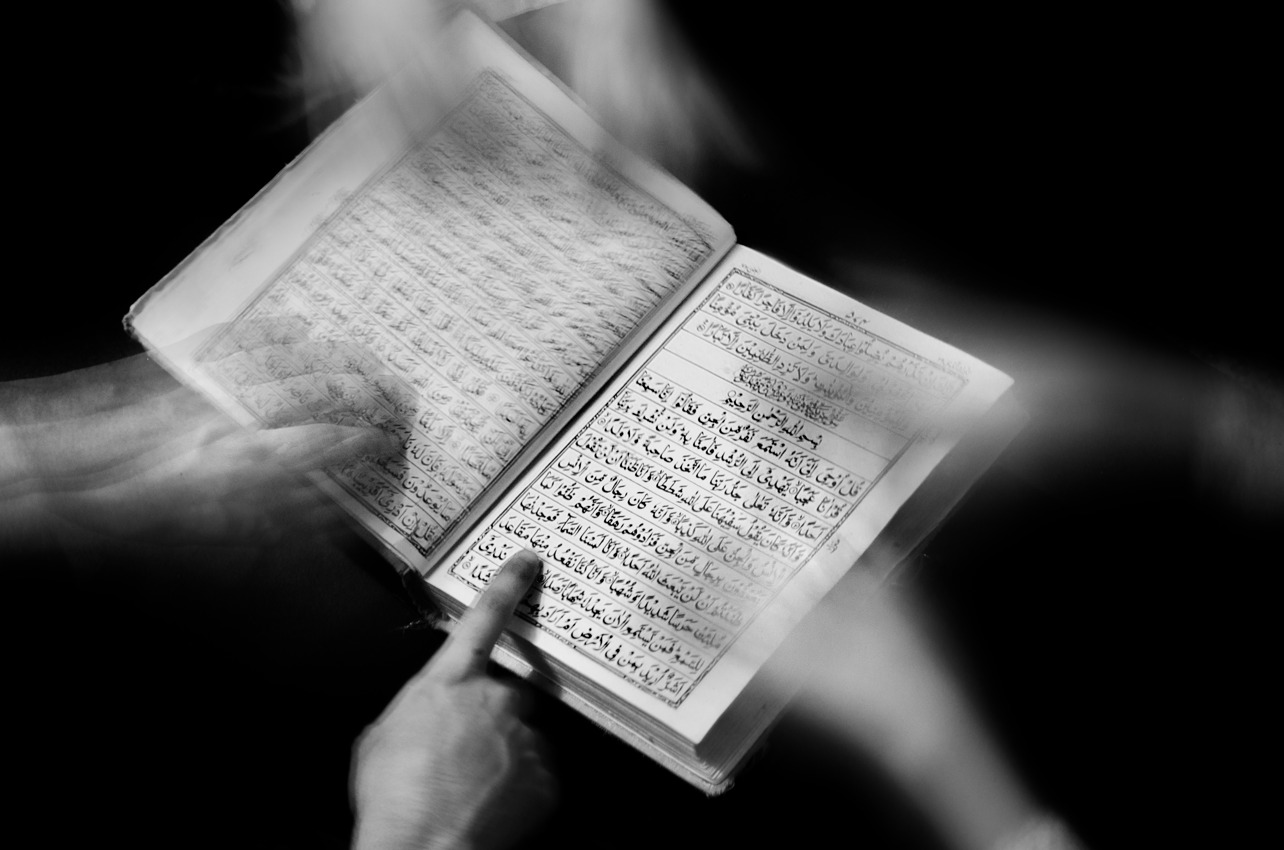

The project is both artistic and archival, exploring Urdu’s legacy, its distortions, its societal contributions, and the emotional inheritances it carries. Rooted in the lived realities of South Asia, it responds to the steady disappearance of Urdu from public spaces, cultural institutions, and mainstream consciousness in India. Once a language of politics, philosophy, and immense romance, Urdu today is increasingly pushed to the margins and associated solely with a Muslim identity under rising far-right narratives. Though it has always been a Hindustani language. This project emerges from the urgency to remember, reclaim, and reimagine.

Through constructed photography, art direction, filmmaking techniques, heritage interventions, 22-carat gold, and handwritten calligraphy, I explore Urdu’s layered histories via a personal narrative framed as a fictional letter from a father to his daughter, Zainab. Seen collectively, the artworks form a single continuous letter, yet when encountered individually, each stands as a letter unto itself, an intimate fragment of the larger narrative. The works merge luxury, storytelling, dying craftsmanship, history, and archive and are developed with the support of Ms. Shabana Faizal, the Faizal and Shabana Foundation, and Qissagoi.

The Capitalyst: A lot of your work sits at the intersection of personal history and collective trauma. What do you see as your larger purpose as a photographer when you take on subjects this emotionally charged?

Taha: For me, my art and photography is an act of remembrance. It is a way of holding space for what is being erased, what is wounded, and what must never be forgotten. My work emerges from personal history but extends far beyond it, carrying the weight of collective memory, marginalisation, loss of language, and the silent grief of communities like mine. When I create an artwork or a collection, I see it as building an archive for the future so that when history is rewritten, something still remains for the future generations. In emotionally charged subjects, my responsibility is to engage with sensitivity rather than spectacle, to create work that listens as much as it speaks, and to invite reflection rather than consumption. Working across cultures has expanded my vocabulary, not just visually, but ethically. It has taught me to listen before creating, and respect before executing.

I wish my work to become a mirror to the society, urging us to question who we are becoming as a society, how easily we forget, and how dangerously we repeat what we failed to learn. If my work can spark even a small pause, a discourse, a shift in perspective, or a moment of self reflection for someone who sees themselves in it, then I believe I have fulfilled my purpose. It’s all about changing perspectives and that’s where the change begins.

The Capitalyst: In your view, what is the role of photography today when it comes to addressing historical wounds, cultural memory, or the evolving identity of contemporary India?

Taha: Art and Photography, placed in contemporary India, for me, is a form of witness and reclamation. As a Muslim artist in contemporary India, I use my art to challenge erasure, polarisation and marginalisation of my community. It allows me to return to my histories, reclaim my Muslim identity and reflect upon the secular nature of my country India, bringing them back into collective memory.

The Capitalyst: Your work has been shown internationally and recognised through awards and residencies. How have these experiences shaped the way you think about responsibility, representation, and narrative?

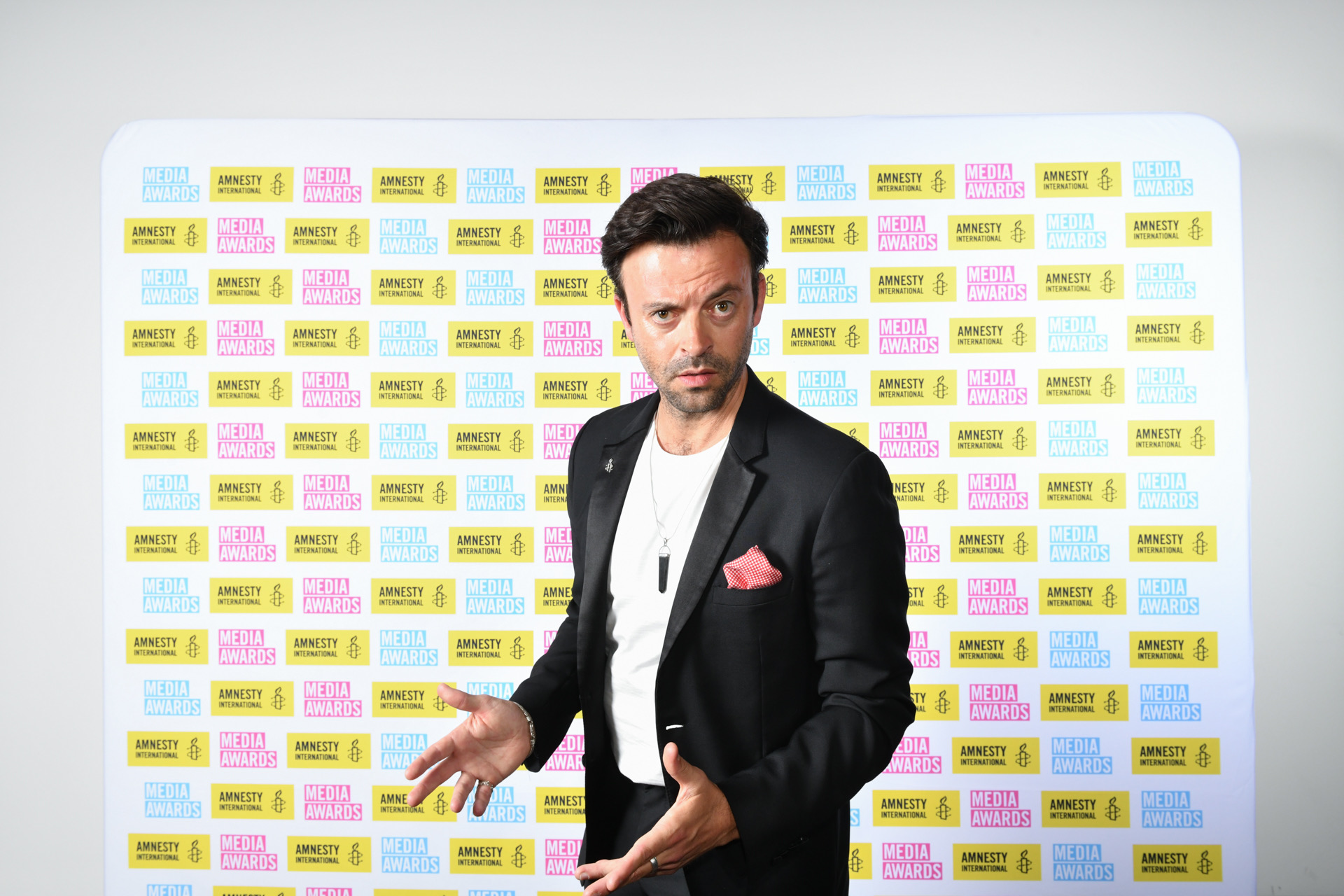

Taha: Grateful, is the word. Recognition is humbling, but I’ve always viewed it less as an accolade and more as a responsibility. Whether it is being named in Forbes 30 Under 30 Asia, the Gucci UN Regenerative list of 100 next-gen leaders, exhibiting internationally, or being part of global conversations each moment reminds me that South Asian stories, and my identity as a Muslim, belong on the world map. These recognitions validate the communities, memories, and geographies I represent, while also grounding me in accountability to them. Working across cultures from photographing in India to installing work in America and Taiwan has taught me patience, humility, empathy, and the importance of giving back. These experiences have changed me deeply; they’ve made me laugh, cry, learn, unlearn, and evolve, not just as an artist but as a human being. And amid all of this growth, these honours continually remind me to stay rooted, keep learning, and keep amplifying voices and stories from South Asia with honesty and intention.

The Capitalyst: You often work with stories that are fragile, painful, or politically sensitive. How do you navigate ethics, empathy, and your own emotional boundaries while documenting them?

Taha: For me, working with fragile or politically charged stories begins with a sense of responsibility towards the people, to the memory, and to the truth. I never approach a subject as an observer looking in, but as someone who carries a shared history. Being a Muslim artist in contemporary India means that many of these wounds are personal, not distant. So ethics and empathy are not concepts I apply later, they are the core foundation.

I spend time listening, building trust, and understanding before I even pick up the camera. Consent, dignity, and agency are core to my practice. I am always conscious that these stories do not belong to me, they belong to these people and communities where I am only a medium. I try to tell the stories these people and communities want them to be told. Some stories require silence, slowness, and sometimes the strength to not photograph at all.

Emotionally, it can be heavy. But that’s where my commercial practice comes in to rescue. My work is never to sensationalise pain, but to soften the distance between viewer and my story, to humanise what is repeatedly dehumanised, and to honour voices history tries to erase. Ethics, to me, is not just about how we document, but how gently we hold what we create.

The Capitalyst: Looking ahead, what new projects or themes are you excited to explore, and how do you hope your future work continues to provoke questions, dialogue, and reflection?

Taha: Looking ahead, I’m most excited for the release of my upcoming project, Zarrēn Payaam-e-Urdu: The Aureate Message of Urdu, which I’ve been building for over three and a half years. The project is planned to open next year and incorporates mediums like constructed photography with handwritten calligraphy and 22 carat Gold painting. I am also looking for opportunities to make my installation ‘Drawn into two which way Home?’ travel to institutions, biennales, festivals, and galleries across the world, and eventually return home to India. I want my audiences to not just view the work, but step into it, breathe inside it, and feel the tenderness and urgency of intergenerational trauma of Partition and today’s realities.

Parallel to this, I am preparing to step into filmmaking, a medium that allows me to reach a wider audience. I’ve written a script that I hope to direct soon, rooted again in inheritance, language, and the politics of belonging.

In the coming years, I want to keep experimenting fearlessly, moving between photography, installation, cinema, and archival interventions. My intention is that my work continues to provoke questions, spark dialogue, and create spaces of reflection around identity, erasure, resilience, and reclamation. I want my art to not just be seen but to stay with my audience.

Photos Credit: Taha Ahmad