In the world of haute cuisine, three small symbols hold the power to make or break careers, fill reservation books years in advance, and transform unknown chefs into culinary legends overnight. Yet these prestigious Michelin stars did not emerge from a council of master chefs or a centuries-old gastronomic institution. Their origin story is far more unexpected: they were born from the brilliant, if bizarre, marketing strategy of a French tire company looking to sell more rubber.

The Birth of a Guide: When Cars Were a Luxury

The year was 1900, and automobiles were still a novelty reserved for the wealthy and adventurous. In France, fewer than 3,000 cars navigated the country’s roads. Two brothers, André and Édouard Michelin, had founded their tire company eleven years earlier and faced a peculiar challenge: how do you grow a business when your potential customer base could fit inside a modest concert hall?

Their solution was audaciously forward-thinking. If more people could be encouraged to drive, they reasoned, more tires would inevitably wear out and need replacing. The Michelin brothers needed to make driving not just practical, but irresistible.

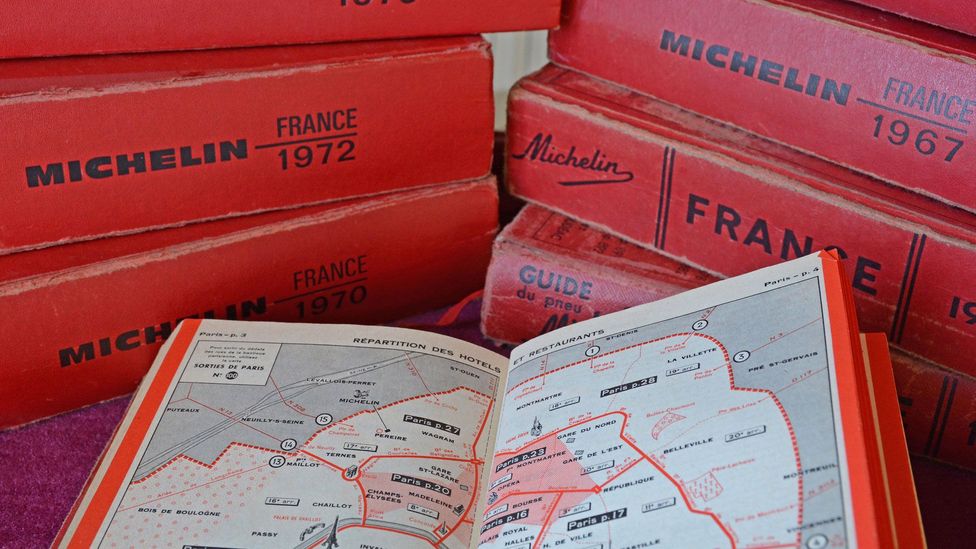

Enter the Michelin Guide—a compact, red-covered booklet distributed free of charge to motorists. This was not merely a list of restaurants; it was a comprehensive manual for the intrepid road traveller. Early editions included practical information like how to change a tire, where to find gas stations, and listings for mechanics, hotels, and yes, places to eat. The guide was designed to make automobile travel less daunting and more appealing, transforming driving from a mechanical challenge into an adventure.

From Free Handout to Must-Have Publication

For two decades, Michelin distributed their guide freely, treating it as a promotional tool. But in 1920, the story takes a fascinating turn. According to company lore, André Michelin visited a tire shop and discovered his guides being used to prop up a workbench. The sight apparently offended him deeply. “Man only truly respects what he pays for,” he reportedly declared.

This moment of wounded pride led to a revolutionary decision: Michelin would begin charging for the guide and, more importantly, would reimagine it entirely. The company removed the advertisements that had cluttered earlier editions and began paying anonymous inspectors to visit and review establishments with rigorous standards. What had been a free marketing pamphlet was evolving into an authoritative publication that commanded respect—and a purchase price.

The Star System Illuminates

The iconic star system did not appear until 1926, and it initially featured only one star, indicating a “fine dining establishment.” The full three-star hierarchy emerged in 1931, establishing the rating system that would become legendary:

One star indicated “a very good restaurant in its category”—a place worth stopping at if you were passing by.

Two stars meant “excellent cooking, worth a detour”—suggesting diners should plan their route to include this establishment.

Three stars represented “exceptional cuisine, worth a special journey”—the pinnacle of gastronomic achievement, restaurants so extraordinary they justified trips of hundreds of miles.

This gradation was brilliant in its simplicity and perfectly aligned with Michelin’s original goal: getting people to drive more. Each additional star represented not just culinary excellence, but a justification for longer journeys—and consequently, more tire wear.

The Inspectors: Guardians of Gastronomic Standards

Central to the Michelin Guide’s credibility was its corps of anonymous inspectors. These culinary detectives, recruited from hospitality schools and the restaurant industry itself, maintained strict secrecy about their identities. They paid for their own meals, visited restaurants multiple times, and evaluated establishments using consistent, rigorous criteria: quality of ingredients, mastery of cooking techniques, the chef’s personality as expressed through cuisine, value for money, and consistency over time.

The mystique surrounding these inspectors became part of the Michelin mythology. Restaurant owners and chefs learned to scrutinize solo diners who seemed particularly attentive to their food, wondering if they were serving an inspector who could change their establishment’s destiny with a pen stroke.

When Tires Met Prestige

By the mid-20th century, something remarkable had happened: the Michelin star had transcended its commercial origins to become the industry’s gold standard. Chefs who had trained for decades in classical French technique now dreamed not of opening successful restaurants, but of earning those elusive stars. The tire company’s marketing tool had somehow become the ultimate arbiter of culinary excellence.

The transformation was so complete that most diners today don’t even know about the guide’s automotive origins. They see the Michelin star as purely gastronomic, divorced from any association with radial tires or tread patterns. This represents perhaps the most successful brand evolution in marketing history: a symbol that completely shed its commercial context to become synonymous with excellence itself.

The Weight of Stars: Glory and Pressure

The influence of Michelin stars grew to almost absurd proportions. Restaurants that earned three stars saw reservations booked months in advance. Chefs became celebrities. Tourism boards promoted their regions based on Michelin-starred restaurant counts. The French economy reportedly gained billions from culinary tourism driven partly by Michelin recommendations.

But the system’s power brought crushing pressure. Tales emerged of chefs suffering breakdowns over lost stars, with some establishments closing rather than operating with diminished ratings. The most tragic story involved French chef Bernard Loiseau, who died by suicide in 2003 amid rumors he might lose his third star (though Michelin maintained he was never at risk).

These incidents raised questions about whether a tire company’s rating system should wield such psychological and economic power over the culinary world, yet they also testified to just how completely the Michelin star had become the ultimate symbol of gastronomic achievement.

A Marketing Strategy That Changed Fine Dining Forever

Today, the Michelin Guide operates in over 40 territories worldwide, from Tokyo to São Paulo to Dubai. It has spawned countless imitators and remains the most influential restaurant rating system globally. The original business strategy—getting people to drive more to wear out tires—seems almost quaint now, a footnote to a cultural institution.

The Michelin star’s evolution from marketing gimmick to culinary holy grail represents an extraordinary case study in brand building. What began as a calculated strategy to boost tire sales became something far more significant: a symbol that shaped modern fine dining, influenced generations of chefs, drove culinary innovation, and created a common language for discussing gastronomic excellence worldwide.

The next time you see those elegant stars beside a restaurant’s name, remember: you are looking at perhaps history’s most successful marketing campaign—one that worked so brilliantly it transcended marketing altogether to become something genuinely meaningful. The Michelin brothers wanted to sell tires. Instead, they accidentally created the Olympics of fine dining.