The Capitalyst: You grew up surrounded by literature, visual culture, and storytelling. How did those early influences shape the way you think about ornament, colour, and narrative before you ever began making jewellery?

Alice Cicolini: I think there is a strong link between where I am now and the home life I had as a child; this is constantly reemerging in my design approach. I was born in London, and lived in the same house all my childhood. I grew up surrounded by books, experimental gardening and love; there was a stillness and consideration that defines the pace at which I now like to work. As a result, I believe in the power of objects to retain and emit memory … on a personal and social level. The pace, commitment, expertise, and contemplation that the handmade demands results in objects that radiate, which speak to us and communicate for us on so many levels.

I love storytelling – all of my career has been about this from theatre, through curating & writing to where I am today. I’m inspired by beauty and superlative craftsmanship, and I want to tell people the story of why these things are important for our culture and our soul. But for myself, it’s my poetry, my pleasure, an expression of my femininity and playfulness. I’ve read countless fairy tales as a child and an adult, dark and light, Western & Eastern, and that little bit of magic …. there’s an element of that in my work too I hope.

The Capitalyst: Before establishing your jewellery practice, you worked as a curator and cultural producer. What prompted the shift from interpreting objects and exhibitions to designing jewellery yourself, and what early project marked that turning point?

Alice Cicolini: Society often speaks about fashioning the future, an idealized concept of looking forward that is very human but is also bound by the present and the past, the way in which we see and filter things around us, reading the runes. For me, I am fascinated by the way in which our histories shape us; backcasting rather than forecasting if you like. Philosopher Walter Benjamin talked about human experience as a labyrinth, where past, present and future fold on top of each other, one informing the other. This way of reading the world feels much more fertile to me than chasing a future that is actually just the present in utopian clothing. Design is curating, juxtaposing, story telling, tasting, smelling, touching, painting, dreaming … the first time I started to feel I was finding my design voice (because that is what this is for me), I experienced that very much as a physical feeling, like the electricity of powerful energy coursing through me, an embodied sensation.

The turning point of the evolution from curation to jewellery was really the death of my mother, and the sense that my purpose was connected to communicating the power of the handmade, as a designer rather than a commentator. It was my friend and mentor Simon Fraser, course director MA Jewellery at Central St Martins, who helped me to see that jewellery was a place where you could still create a hybrid identity creatively -‐ part fashion, part craft, part industrial design, it was certainly not as formulaic a place to inhabit as fashion at that point. And this connected my to a very brief period of working for Andrew Grima in the late nineties; untrained formally, his immense creativity taught me to understand that there many ways to be a jeweler, and to be brave.

The Capitalyst: India became a foundational reference point in your work. What was it about your first encounters with Indian craft – particularly enamel and stone-setting—that made you realise this would be central to your practice rather than a temporary influence?

Alice Cicolini: I was originally very inspired by a jewellery box I saw at the Mehrangir Fort Museum in Jodhpur. The caption stated, rather enigmatically, that the box would have contained all the items needed to perform solah shringar. This lead me on a journey through Indian cultural practice from the legendary Kapila Vatsyayan to Usha Balakrishnan, via all sorts of wonderful stories of the lives of regal women! Basically, solah shringar is an adornment ritual, of sixteen stages, and includes both literal objects (rings, bracelets, necklaces), but also layers of sensory experience – scent, sound, tactility – and methods of building those layers, bathing rituals and so on. I felt this was powerfully evocative. I wouldn’t say I had even scratched the surface of where it will take me, but I have my whole career!

The Capitalyst: Many of your collections reinterpret architectural and textile traditions from regions such as Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. How do you approach transforming these sources into contemporary jewellery without treating them as decorative quotation?

Alice Cicolini: I think because I’m drawing on these sources as ways of communicating with the world, ones that have ancient roots. I’m fascinated (and was as a fashion historian too) with clothing and adornment as a way of communicating your identity, often your location, your work – even your determination to not be interested in fashion or how you look says something about you. In Indian & Japanese textile traditions, and traditional garments, these semiotics are still very current, but also poetic and nuanced. So its not there as a pretty picture, its there because its communicating a story about beauty principally, but also about resonance.

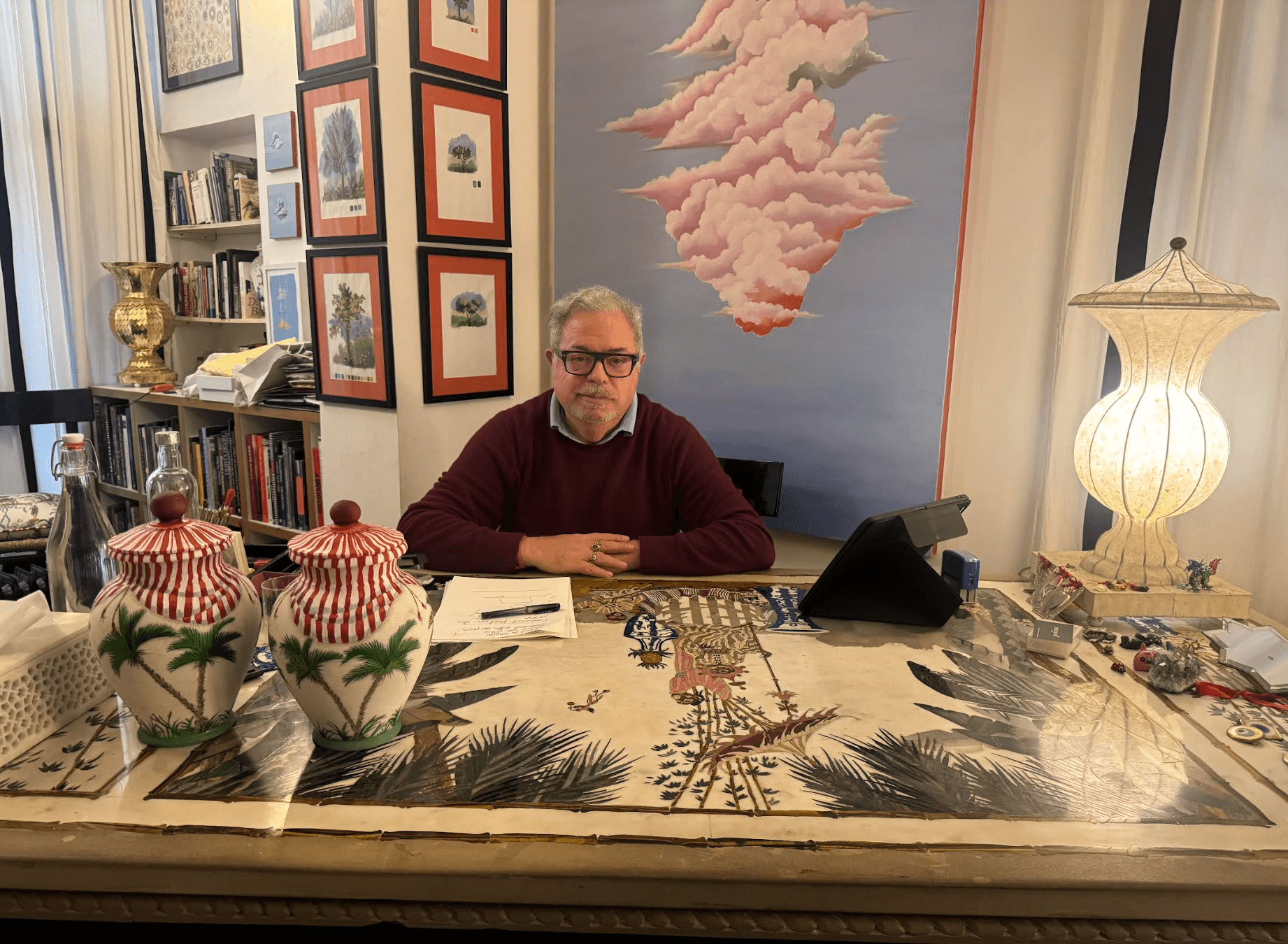

The Capitalyst: Collaboration with Indian master craftspeople sits at the core of your process. How does a collection typically evolve from research to hands-on experimentation in the workshop?

Alice Cicolini: This has changed over the years. What I would say is that as a place to start, spending significant time with the people who make your work is absolutely critical to having a rich exchange that is respectful of their artistry and much more likely to get you where you want to be. My collections evolve as a consequence of my love of cultural heritage, and also my love of enamel as a tradition. Equally I’m inspired by how to push those traditions with new ways of using the material, and developments in the material itself and therefore what it can do. All of these is only possible through dialogue, so I supposed the process is an oscillation between the tactile, the visual and the spoken creative process.

The Capitalyst: Colour and geometry are structural elements in your work. How do you develop colour systems for a project, and what role do proportion and scale play in shaping the final pieces?

Alice Cicolini: Joseph Albers believed that holding 4 colours in harmony was one of the most complex processes within the artist’s remit. What looks simple is really not at all. I don’t know that I think of it as a system. It’s really about what feels right – and the stones also play an important role because they add a textural dimension that is different from the gold and the enamel. Often the pattern or the technique defines the scale … just giving something enough of a canvas to breathe. But of course in the end these objects are for wearing, so I’ve learnt to be more considered about weight over the years!

The Capitalyst: Your jewellery often feels architectural—designed not just to be worn, but to occupy space on the body. How does your curatorial background influence the way you think about jewellery as spatial objects?

Alice Cicolini: I do tend to look at the object as an artwork, and I think enamel lends itself to that because it fosters a way of looking at jewellery that considers the back is as important as the front. So all the angles you might view something more become a canvas. Maybe that where it comes from.

The Capitalyst: Ethical production and craft preservation are integral to your practice. How do these values actively shape the decisions you make when developing new collections?

Alice Cicolini: For me its all about sustainable culture, to which making traditions significantly contribute in places such as Jaipur, Benares, Kolkata, Mumbai – and also London, Birmingham, New York, LA and other great cities of making such as Paris (and many more of course). Sustainable materials and extraction practices are critically important to our future on the planet, but equally unless we are still able to create resonant, powerful and beautiful objects with those materials, it feels to me that those questions of good material provenance are really without foundation.

The Capitalyst: Looking ahead, which new directions or regions of craftsmanship are you most drawn to exploring, and what principles continue to anchor your work across every project?

Alice Cicolini: My style is really about collaboration and juxtaposition, about craftsmanship and heritage, and colour. I also take quite a curatorial approach to my work obviously! There is a lot of narrative behind the collections. So I hope people will fall in love with the stories behind the design, behind the people who made them, behind the techniques and heritage of the craftsmanship – and add their own stories to the gems as they become part of their lives. I think the number of craft techniques I work with might grow, but the principals of my practice and the approach to creating the work will remain the same.

That approach is based on the concept of slow luxury, celebrating the beauty of ancient mastercraft and privileging artisanship alongside fine materials. In a world of fast luxury, the challenge is to express the value of alternative choices to a wide audience but I am extremely passionate about finding a way to do that.