The year was 1982. Dietrich Mateschitz sat in a Bangkok hotel room, exhausted and irritable. As a traveling salesman for Procter & Gamble’s toothpaste division, he had grown accustomed to the fog of jet lag, that peculiar misery of being awake when your body screams for sleep. But on this sweltering Thai night, something changed.

A colleague handed him a small glass bottle of Krating Daeng, a local tonic that truck drivers and factory workers swore by. The liquid was syrupy, medicinal, and unpleasantly sweet. Mateschitz grimaced as he swallowed it. Then, within minutes, the fog lifted. His mind sharpened. The exhaustion that had weighed on him like a wet blanket simply evaporated.

Most people would have said “thanks” and moved on with their lives. Mateschitz saw the future.

From Bangkok Streets to Austrian Alps

Krating Daeng (which translates to “red gaur,” a species of wild cattle) had been around since 1976. Its creator, Chaleo Yoovidhya, was a Thai pharmacist who had studied the energy tonics that manual laborers drank to survive 12-hour shifts. His formula was straightforward: caffeine for alertness, taurine (an amino acid) for endurance, B-vitamins for metabolism, and sugar to mask the taste of everything else.

The drink sold well in Thailand, but it was a working-class product. Cheap. Unglamorous. Something you grabbed at a 7-Eleven before your night shift, not something you would order at a bar.

Mateschitz saw past the brown bottle and medicinal taste. He saw Vienna’s nightclubs. He saw Munich’s all-night libraries. He saw a generation of young Europeans who worked hard and played harder, who needed fuel but wanted style.

In 1984, he pitched Chaleo an audacious idea: Let me take your formula to Europe. We will split the company 50-50. Each man invested $500,000. They tweaked the recipe, adding carbonation to create a lighter, crisper drink that Western palates might actually enjoy. They poured it into sleek silver-blue cans and designed a logo featuring two red bulls charging toward a sun. They called it Red Bull.

In 1987, they launched in Austria with a tagline that would echo for decades: “Red Bull Gives You Wings.”

Year one sales: one million cans. Not bad. Not explosive. Just the beginning.

The American Invasion

When Red Bull finally received FDA approval in 1997, they could have rushed into Walmart and Target. Instead, they deployed a ground force that looked more like a youth movement than a sales team.

Picture this: you’re studying for finals at UCLA’s library at 2 AM. You’ve had three coffees and you’re still fighting sleep. Suddenly, attractive twenty-somethings appear carrying silver cans. “You look like you could use some energy,” one says, handing you a cold Red Bull. “It’s free.”

These were not salespeople. They were “brand ambassadors,” mostly college students, driving cars with giant Red Bull cans mounted on the roof. They showed up at gyms before dawn, skateparks on weekends, indie rock concerts at midnight. They gave away millions of free cans, targeting not the masses but the tastemakers: DJs, artists, athletes, entrepreneurs.

The strategy created organic word-of-mouth. When someone bought their first Red Bull (at $2.50, expensive for the late 1990s), it wasn’t because they saw a commercial. It was because their friend, whose opinion they trusted, told them it was amazing.

U.S. sales in 1998: one million cans. By 2000: one billion cans. The hockey stick growth was so dramatic that industry analysts initially thought the numbers were wrong.

Beyond Beverages: Red Bull’s Triple Crown of Marketing Mastery

While most brands were buying billboards, Red Bull was building empires across three revolutionary fronts.

Formula One: Where Speed Meets Status

In 2005, Red Bull Racing roared onto F1 tracks, and paddock veterans smirked. A beverage company competing against automotive giants like Ferrari and Mercedes? The joke died quickly. By 2010, they’d claimed their first Constructor’s Championship. By 2024, eight titles sat in their trophy case, with Max Verstappen dominating circuits worldwide. Each race broadcasts Red Bull’s logo to 500 million fans across 180 countries. This wasn’t sponsorship; it was colonization of the world’s most prestigious motorsport.

The Media Empire: Creating Culture, Not Ads

In 2007, Red Bull became a media company. Red Bull Media House produced theatrical films like “The Art of Flight” (2011), a $2 million snowboarding epic that played in actual theaters. The Red Bulletin magazine reached millions. Their YouTube channel accumulated billions of views with extreme sports content. The Red Bull Music Academy, mentoring underground musicians since 1998, launched careers like Flying Lotus’s. They weren’t interrupting culture to sell products; they were manufacturing culture itself, then casually attaching their logo.

Stratos: The Ultimate Spectacle

October 14, 2012. Felix Baumgartner stood 128,000 feet above New Mexico in a Red Bull-branded spacesuit, where the sky turns black and Earth curves below. Then he jumped. For four minutes and 19 seconds, he fell, breaking the sound barrier with his body at 843 mph. Eight million people watched live on YouTube as he deployed his parachute and landed safely. Media coverage generated an estimated $500 million in brand value.

Red Bull Stratos wasn’t about selling energy drinks. It was a declaration: We make impossible things happen. And the world believed them.

The Taurine Wars

Red Bull’s European expansion hit a wall made of bureaucracy and bull testicles. Well, rumors about bull testicles.

European food safety agencies freaked out over taurine, one of Red Bull’s key ingredients. Despite the name, taurine wasn’t extracted from bulls: it was synthesized in labs. But the myth persisted: “It’s got bull semen in it!” Regulatory bodies in France, Denmark, and Norway banned or restricted the drink. Germany required warning labels.

Mateschitz could have reformulated. Instead, he fought, funding scientific studies proving taurine’s safety while simultaneously using the controversy as free publicity. Banned in France? Perfect. French youth smuggled it across borders. Nothing makes a product more desirable than telling people they can’t have it.

By 1997, Red Bull was legal across most of Europe, and annual sales topped 300 million cans. The brand had cultivated an outlaw mystique while building a war chest for the real conquest: America.

From Bangkok to Everywhere

What started with a jet-lagged salesman in a Bangkok convenience store became a blueprint for building modern brands. Red Bull showed that you don’t need to be the cheapest or even the best tasting. You need to stand for something that matters to people.

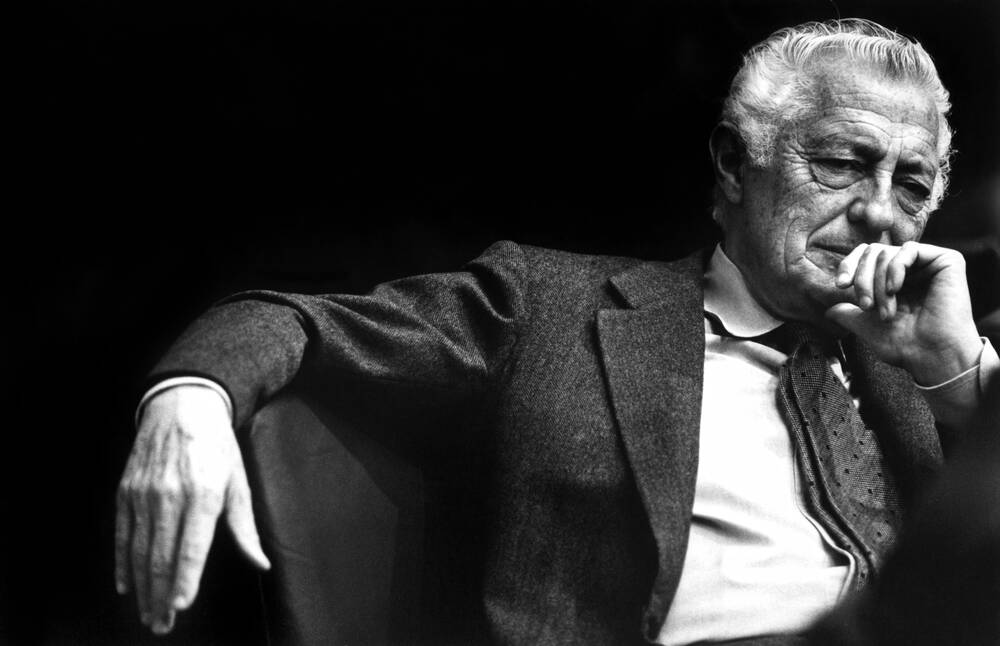

Dietrich Mateschitz died in October 2022 at age 78. He left behind more than a beverage empire. He left behind soccer teams, racing circuits, music venues, and a generation of athletes who built careers under those red bull wings. He left behind a company that proved business could be thrilling, that commerce could fund human achievement at its most audacious.

The Thai pharmacist and the Austrian salesman who shook hands in 1984 couldn’t have imagined their syrupy tonic would fund space jumps and Formula One glory. But perhaps that’s the point. Red Bull’s entire existence argues against playing it safe.

So next time you crack open that silver can, remember: you’re drinking the result of two men who bet everything on a ridiculous idea. They believed people would pay premium prices for an unknown drink if it made them feel extraordinary.

Turns out, they were right. And forty years later, the bull is still charging.